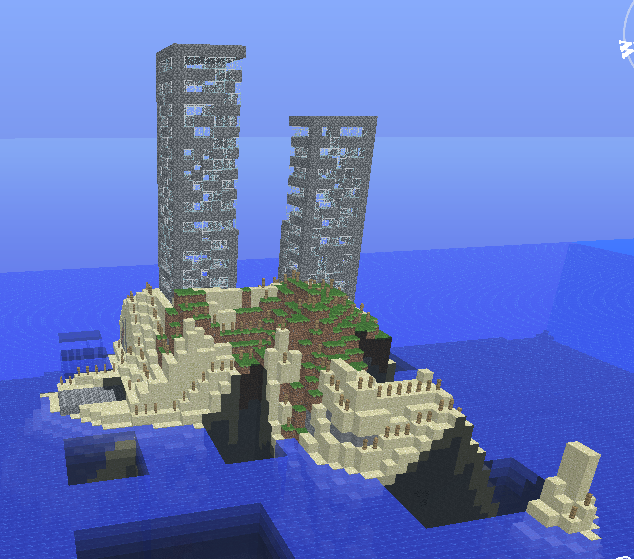

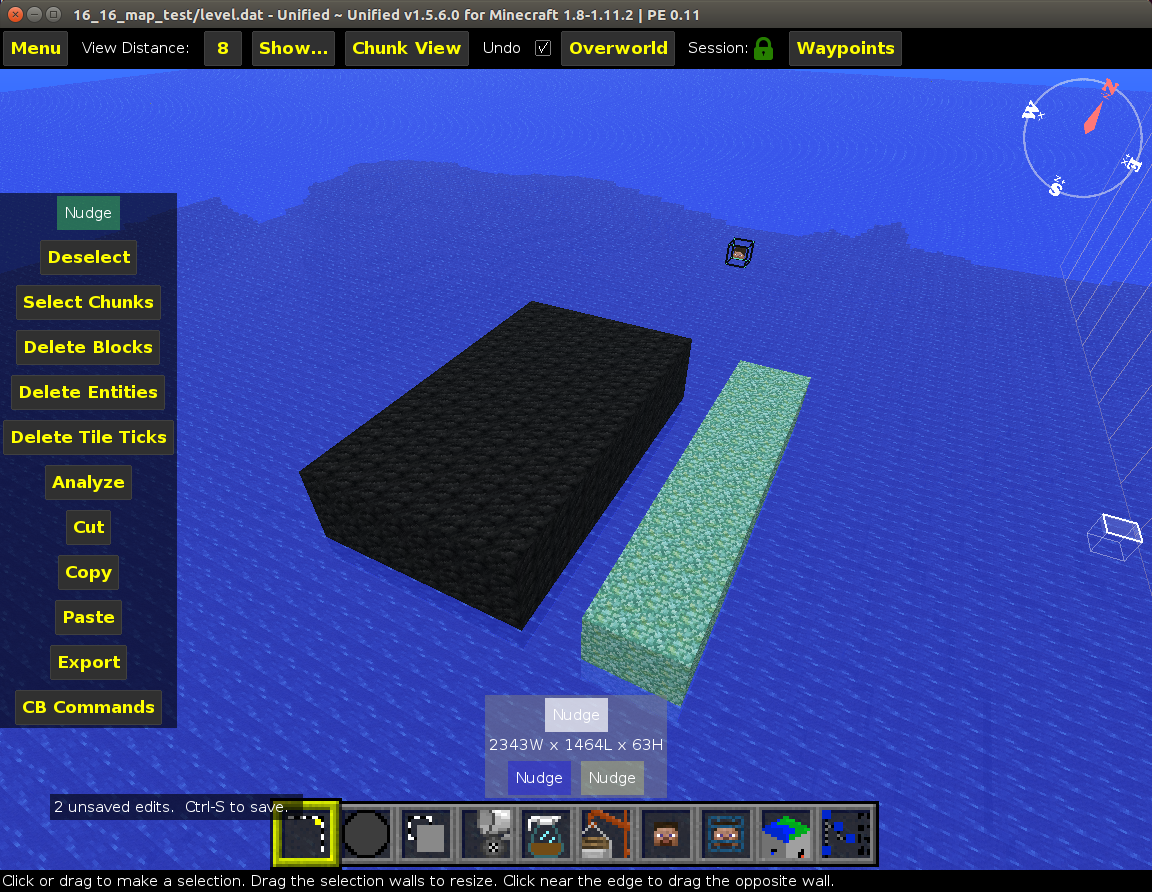

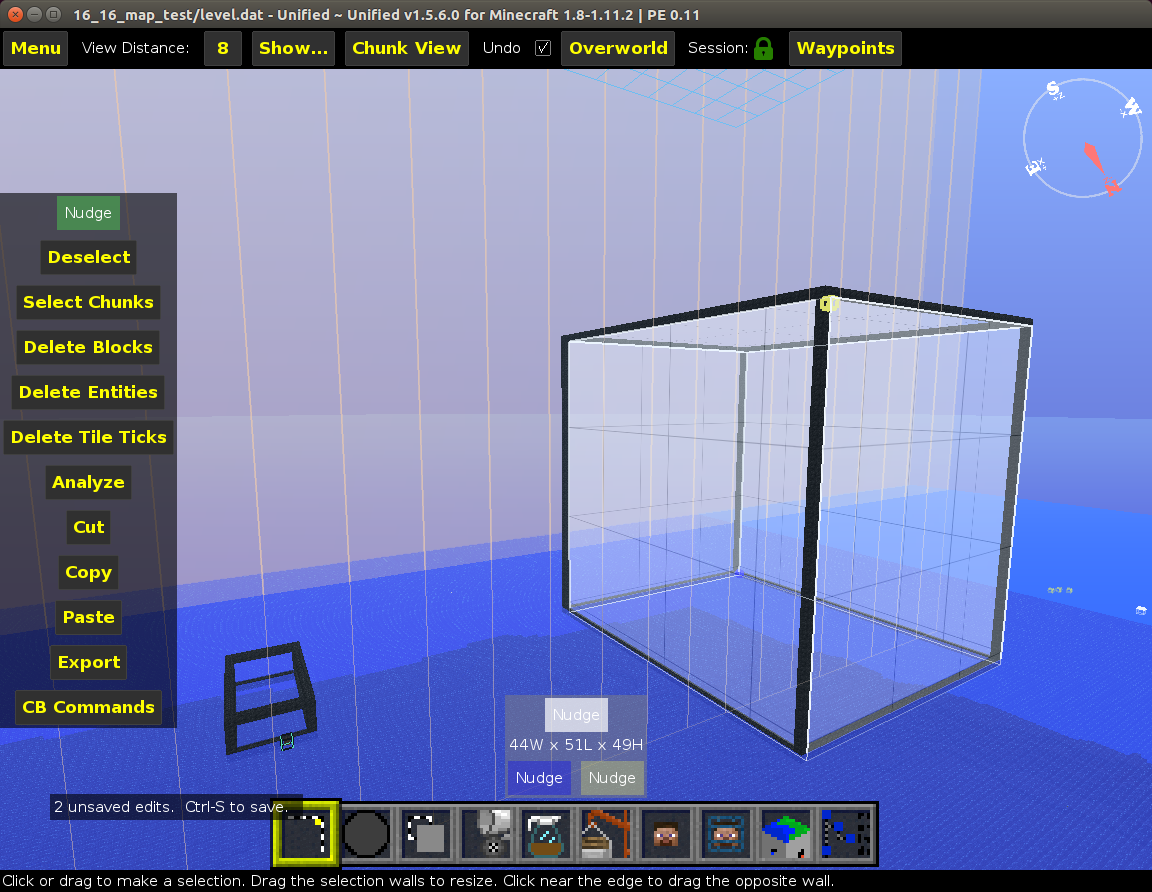

In this case we want to take the user’s selection and draw blocks along the edges, an example can be seen in figure four. The complexity for this problem is creating a function that will properly draw lines. Specifically, it is necessary to make sure it can draw diagonal lines for the sake of completeness.

The main difficulty in this problem is making sure every direction a line can move is accounted for. The list is quite long but mainly requires some attentiveness on our our part when defining all the possibilities.

directions = [(1,0,0),(-1,0,0),(0,1,0),(0,-1,0),(0,0,1),(0,0,-1),\

(1,1,0),(-1,1,0),(1,-1,0),(-1,-1,0),(0,1,1),(0,-1,1),\

(0,1,-1),(0,-1,-1),(1,0,1),(-1,0,1),(1,0,-1),(-1,0,-1),\

(1,1,1),(-1,1,1),(1,-1,1),(1,1,-1),(-1,-1,1),(-1,1,-1),\

(1,-1,-1),(-1,-1,-1)]

We now have the task of using the directions array to draw the line along the shortest path from the starting point to the end point. I first wrote this with a recursive method, where it would find the point closest, with the

manhattan distance,

and then draw a block. It would recursively call itself again, drawing a block at the next closest point, until it had reached the end point. Please note that I did not put in object avoidance into this method as it was beyond the scope of the problem. With the recursive method complete, it became clear a while loop would be just as clear with minimal code changes and be more performant since

tail recursion

is not supported by Python.

Once drawing a line was completed, the last step was to use the vertices I defined in the section dedicated to drawing materials in all eight corners to draw the edges as well. The code for the filter is below.

from pymclevel import alphaMaterials, MCSchematic, MCLevel, BoundingBox

from pymclevel.box import Vector

from mcplatform import *

inputs = (

("Replace All", "label"),

("Material", alphaMaterials.CoalBlock),

("Creator: Colan Biemer", "label")

)

def vector_equals(v1, v2):

return v1.x == v2.x and v1.y == v2.y and v1.z == v2.z

def manhattan_distance(start, end):

return abs(end.x - start.x) + abs(end.y - start.y) + abs(end.z - start.z)

def draw_block(level, x, y, z, material):

level.setBlockAt(x, y, z, material.ID)

level.setBlockDataAt(x, y, z, 0)

def draw_block(level, point, material):

level.setBlockAt(point.x, point.y, point.z, material.ID)

level.setBlockDataAt(point.x, point.y, point.z, 0)

def fill_box(level, origin, size, material):

final_x = origin.x + size.x

final_y = origin.y + size.y

final_z = origin.z + size.z

for x in range(min(origin.x, final_x), max(origin.x, final_x)):

for y in range(min(origin.y, final_y), max(origin.y, final_y)):

for z in range(min(origin.z, final_z), max(origin.z, final_z)):

draw_block(level, x, y, z, material)

def draw_line(level, start, end, material):

directions = [(1,0,0),(-1,0,0),(0,1,0),(0,-1,0),(0,0,1),(0,0,-1),\

(1,1,0),(-1,1,0),(1,-1,0),(-1,-1,0),(0,1,1),(0,-1,1),\

(0,1,-1),(0,-1,-1),(1,0,1),(-1,0,1),(1,0,-1),(-1,0,-1),\

(1,1,1),(-1,1,1),(1,-1,1),(1,1,-1),(-1,-1,1),(-1,1,-1),\

(1,-1,-1),(-1,-1,-1)]

draw_block(level, start, material)

while not vector_equals(start, end):

new_s = start + directions[0]

dist = manhattan_distance(start, end)

for i in range(1, len(directions)):

s = start + directions[i]

d = manhattan_distance(s, end)

if d < dist:

new_s = s

dist = d

start = new_s

draw_block(level, start, material)

def draw_box_outline(level, box, material):

point_1 = box.origin

point_2 = Vector(box.origin.x + box.size.x, box.origin.y, box.origin.z)

point_3 = Vector(box.origin.x, box.origin.y + box.size.y, box.origin.z)

point_4 = Vector(box.origin.x, box.origin.y, box.origin.z + box.size.z)

point_5 = Vector(box.origin.x + box.size.x, box.origin.y + box.size.y, box.origin.z)

point_6 = Vector(box.origin.x + box.size.x, box.origin.y, box.origin.z + box.size.z)

point_7 = Vector(box.origin.x, box.origin.y + box.size.y, box.origin.z + box.size.z,)

point_8 = Vector(box.origin.x + box.size.x, box.origin.y + box.size.y, box.origin.z + box.size.z)

draw_line(level, point_1, point_2, material)

draw_line(level, point_1, point_3, material)

draw_line(level, point_1, point_4, material)

draw_line(level, point_2, point_6, material)

draw_line(level, point_4, point_6, material)

draw_line(level, point_3, point_7, material)

draw_line(level, point_4, point_7, material)

draw_line(level, point_7, point_8, material)

draw_line(level, point_6, point_8, material)

draw_line(level, point_8, point_5, material)

draw_line(level, point_5, point_2, material)

draw_line(level, point_5, point_3, material)

def perform(level, box, options):

draw_box_outline(level, box, options["Material"])